Intergenerational and transnational caregiving in Filipino families

How the pandemic has reshaped the Filipino Canadian experience

The son of Filipino parents, Ilyan Ferrer lived a childhood common among families in racialized immigrant communities: he spent a lot of time being looked after by his grandparents so his parents could work to provide a better life for the family. Now an assistant professor in the School of Social Work at Carleton University, Ferrer is taking a closer look at that dynamic, exploring how the complex web of intergenerational and transnational caregiving shapes the identities of older Filipinos and their families living in and between Canada and the Philippines.

“I didn’t see very much of my own experience reflected in the existing research, so that’s what got me into gerontology,” he says. “I wanted to honour and share stories like what my family went through on a broader scale to resist some of the misconceptions about aging in immigrant communities.”

Dispelling myths about older immigrants

Four generations of Ilyan Ferrer’s family—his grandmother, mother, partner and daughter—demonstrating the intergenerational care that is part of so many Filipino households.

With a SSHRC Insight Development Grant, Ferrer and co-researchers Conely De Leon, Robyn Rodriguez and Valerie Francisco-Menchavez will look at the experiences of older Filipino immigrants, who are often left out of the immigration narrative. Filipino Canadians are the fourth largest racialized group in Canada, but the community is only three to four generations old. As the community continues to grow and build deeper roots, it’s important to ensure the unique stories and cultural traditions of its people are preserved.

Older immigrants play an important part in that preservation, with Ferrer referring to them as “cultural stewards” of their communities. However, they are too often dismissed as having nothing to offer beyond helping to raise their grandchildren.

Another misconception Ferrer aims to dispel is the idea that immigrants and migrants who are no longer of working age are a financial burden to Canada when they arrive. In fact, clauses in visa and immigration policies often require them to be financially dependent on their families. For example, under the Parent and Grandparent Sponsorship program, they aren’t eligible for pensions or other supports for 20 years—and in the case of the Supervisa program, older migrants are always fully dependent on their sponsors.

“I want to disrupt the way we think about aging as an individual experience,” says Ferrer. “It’s an intergenerational one that can involve the whole community.”

Disrupted by the global pandemic

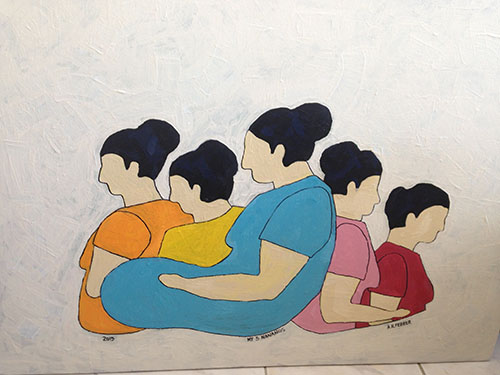

A creative rendering of five women caregivers by Avelino Ferrer, the researcher’s father, representing the care he received in the Philippines by older members of his family.

The team originally planned to interview at least 50 older Filipinos and their families in Calgary and Toronto, then travel to Manila to speak to Filipino Canadians who split time between the two countries—to learn about their physical, emotional and financial care arrangements and relationships. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, those plans had to be put on hold.

But the team quickly realized that the pandemic would also present entirely new avenues of potential study. Most notably, it would allow them to look into the ways restrictions on gathering and travel have shifted the caregiving relationships among these families, particularly those that extend transnationally. They also plan to prioritize intergenerational storytelling and lessons learned about aging and care.

The team is now re-evaluating the focus, methodology and even possible outcomes of the project. One area that may get more focus is how isolation, physical distancing and vaccine inequity are reshaping the realities and dynamics of immigrant families.

“The pandemic has added burden to members of the Filipino community, especially to those with responsibilities both locally and abroad,” says Ferrer, noting that financial remittances from family members living elsewhere make up a significant portion of the Philippines’ gross domestic product (GDP).

Ferrer hopes this research will raise awareness of some of the issues faced by older Filipinos in Canada—in the context of the pandemic and beyond. He also intends for it to support advocacy for changes to immigration and caregiving policies, such as reducing the financial dependency requirements of immigration sponsorship programs, which will help Filipino Canadian families build communities that preserve their social, political and cultural contributions and legacies, both in Canada and abroad.